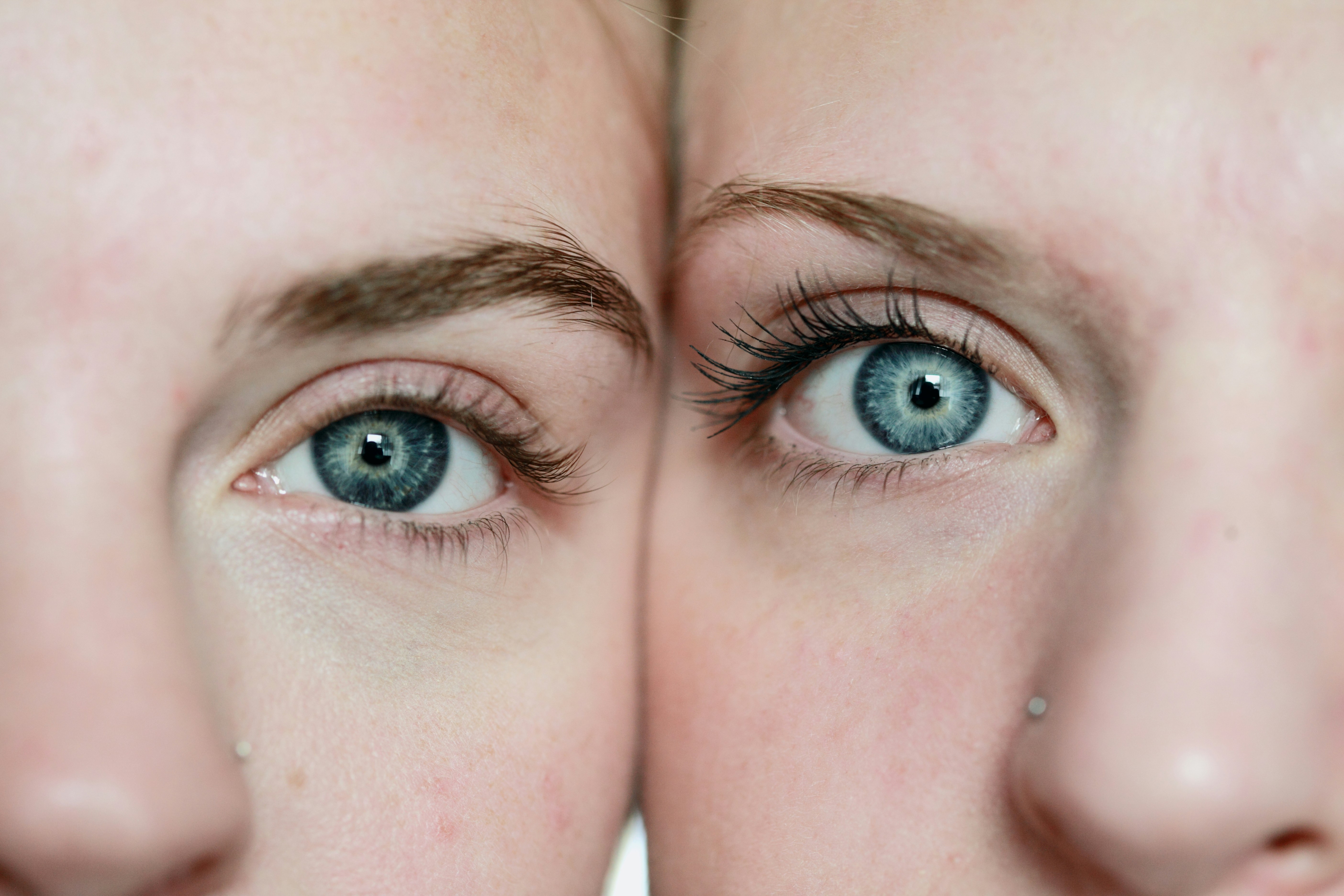

Denmark’s new law granting citizens copyright ownership over their face, body, and voice signals a bold step toward reclaiming personal identity in the age of AI.

Denmark’s new law granting citizens copyright ownership over their face, body, and voice signals a bold step toward reclaiming personal identity in the age of AI.

For the first time, individuals, not corporations or tech platforms, hold the rights to their own biometric likeness. Supporters argue it is a necessary safeguard against deepfakes, exploitation, and unchecked data scraping, even if it introduces major hurdles for AI companies and creative industries.

While experts warn of costs, consent complexities, and potential slowdowns in innovation, Denmark’s law raises a fundamental issue: in an AI-driven world, should control over our likeness belong to individuals or remain in the hands of technology companies?

By giving individuals legal control over the use of their likeness, Denmark has changed how artificial intelligence companies approach training data. AI models that once scraped public photos and videos will need to obtain explicit consent instead.

“If someone owns the copyright to their own face, body, and voice, it directly impacts the way AI can be trained or generate outputs,” said David Hunt, Chief Operating Officer at Versys Media . Hee added that the law “essentially blocks third parties from scraping or replicating your likeness without explicit permission, which could reshape how training datasets are sourced.”

For AI companies, this may mean licensing likeness rights in the same way music or film rights are negotiated. While this could lead to cleaner datasets, it also raises costs and adds new barriers for smaller players.

Critics argue that the law strikes at the heart of creative and marketing industries. Matthew Goulart, Founder of Ignite Digital, warned of its impact on digital campaigns: “If this law spreads, every time we use a client’s likeness in an AI-generated asset, we’d need explicit licensing agreements. Under Denmark’s rule, using that likeness without granular legal clearance could turn a growth campaign into a legal liability overnight.”

This concern is echoed by Gene Genin, CEO of OEM Source, who sees a collision between privacy and creativity: “It may also block how companies and creators can use human likeness which can reduce freedom of creativity in the aspect of media and marketing.”

Practical enforcement is another open issue. In theory, the law empowers individuals to challenge deepfakes and unauthorized likeness use, but in reality enforcement will depend on technological safeguards. Gyan Chawdhary, Vice President at Kontra, Security Compass, explained: “Think of it like the ‘copyright takedown’ system we already see for music or movies, but for your likeness. If someone posts a fake video of you, you could send a request to the platform to take it down—and the platform would have to act quickly or risk fines.”

With extra layers of bureaucracy, some experts fear that protection of online identity will come at a cost of creativity and experimentation.

Opinions differ sharply on whether this law is the start of a larger European shift. Maiocchi believes countries with strong privacy traditions like Germany or the Netherlands may follow. Mircea Dima, CEO of AlgoCademy, is more cautious: “Although this law can be considered an innovative initiative, I am sure that it will take longer to be widely accepted, given that other regions and other legal frameworks also estimate its practical effects.”

At the same time, Denmark’s presidency within the EU Council gives it a platform to influence digital policy debates across Europe. If the law gains traction, it could set a precedent for treating biometric identity as intellectual property.

Whether viewed as a bold leap forward for individual rights or a heavy-handed brake on technological progress, Denmark’s new law highlights a deeper shift: our faces, voices, and bodies are no longer just personal attributes but potential assets in the digital economy.

The question now is whether Europe and the wider world will follow Denmark’s example, or decide that protecting digital identity this way comes at too high a cost to innovation.

Productivity, wellness and focus apps are getting increasingly more popular. However, these tools, created for well-being, could also have a significant, yet hidden, data leak and privacy problem.